|

|

|

Number 49 Merrion Square, a fine Georgian house on the east side of the Square, was built by George Kent some time between the 1790s and 1814. In 1818 it was leased by Robert Way Harty, later Lord Mayor of Dublin. He commissioned the cycle of mural paintings in the two first-floor rooms thought to have been completed c.1820 and which is an exceptional feature of the house. Later enhancements to the house in the 19th century include two elegant Victorian marble chimneypieces installed in those rooms and decorative cast iron balconies outside the first floor windows. The house has been the home of the National University of Ireland since 1912. The National University of Ireland was established in 1908 as a federal university in response to the aspirations of an incipient nation for university education. Over its history, the federation has been outstandingly successful and its academic reputation has grown nationally and internationally. At the beginning, in the region of 1,000 students were spread across four colleges. The first NUI graduates emerged in 1910 when some 300 students were conferred. Today, there are more than 65,000 students in the NUI institutions and over 25,000 NUI degrees and other qualifications are awarded annually. Over time the institutional character and structure of the National University of Ireland have been radically transformed: in addition to the original university, the National University of Ireland now includes four separate self-governing universities. While each university pursues its own strategic mission, all four constituent universities retain and value their common history and shared identity as members of the federal university. |

NUI at 49 Merrion Square serves as the centre of the federal university. This is where that the Senate and the other committees of the University meet, where the NUI executive is based and where the archives of the University are housed. The primary purpose of NUI today is to provide the central forum for the institutions of the National University of Ireland, to promote the interests of the four Constituent Universities and to provide services to them. A secondary purpose served by NUI, using powers granted under its Charter, has been to make its qualifications available to the Recognised Colleges of the University. NUI also has an important cultural role, supporting scholarship and research particularly in areas relating to the Irish language, Celtic Studies and the history and culture of Ireland. National University of Ireland www.nui.ie Constituent Universities University College Dublin www.ucd.ie University College Cork www.ucc.ie National University of Ireland, Galway www.nuigalway.ie National University of Ireland, Maynooth www.nuim.ie Recognised Colleges Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland www.rcsi.ie National College of Art and Design www.ncad.ie Institute of Publin Administration www.ipa.ie Milltown Institute of Theology and Philosophy www.milltown-insitiute.ie Shannon College of Hotel Management www.shannoncollege.com College of a Constituent College St. Angela's College www.stangelas.com |

NUI, 49 Merrion Squareby Dr. Attracta Halpin Registrar, NUI |

|

|

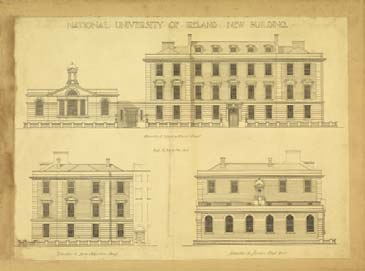

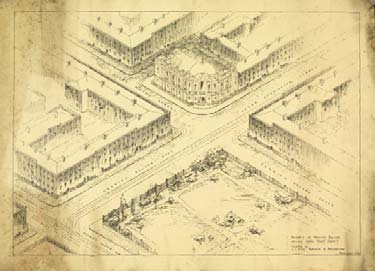

On its foundation, the National University of Ireland took over the buildings of the Royal University in Earlsfort Terrace. In 1909, the Senate agreed to a request from University College Dublin to make part of the building available to the College1 and before long the logic of UCD taking over the whole of the Earlsfort Terrace building became apparent and ownership was transferred to the College2. Nos. 48 and 49 Merrion Square were rented for the National University of Ireland and the University relocated there in 19123. Initially this was intended as a temporary address and premises were acquired in Upper Mount Street (nos. 55 to 62) and in Lower Fitzwilliam Street (nos. 29 and 30) in 1914. Elaborate plans for a university building were prepared and a competition for the design of extensive new premises on this site was instituted, with Mr Charles J. McCarthy, City Architect, as the Assessor4. The scale of the |

proposed development (Senate Room of 1,800 square feet and large meeting and examination hall of 5,000 square feet) reflects a grandeur of vision not unlike that seen in the 1930s Senate House of the University of London. Interestingly in light of the later controversy that would surround the replacement of Georgian buildings in Fitzwilliam Street, it is clear that the intention was to demolish and replace the houses purchased. The instructions to competitors included the following: The style of the architecture and the materials to be employed are left to the discretion of the competitors, but it is essential that the building should be of good architectural character, expressive of its purpose and without unnecessary elaboration. It is desired that Irish materials shall be used as far as possible. The character of the surroundings generally should also be taken into account. |

Figures 1, 2 and 3 above: The winning plans and artist's impression of the buildings preposed for the National University of Ireland 1914.

Figures 1, 2 and 3 above: The winning plans and artist's impression of the buildings preposed for the National University of Ireland 1914. |

|

|

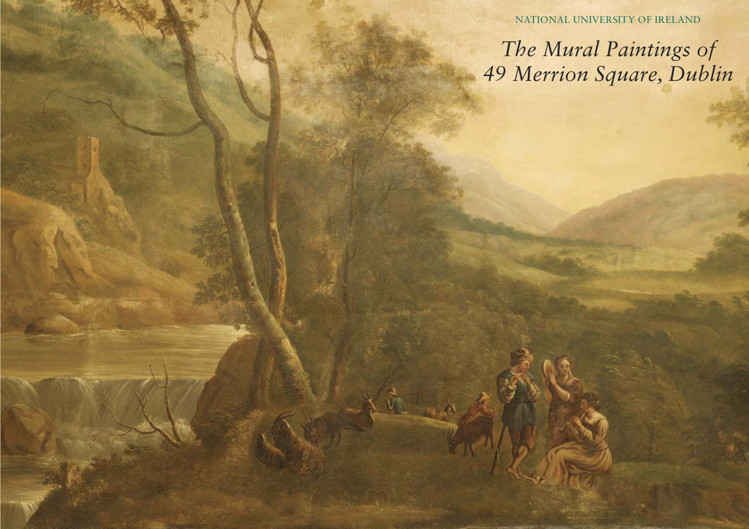

With the First World War casting its shadow, NUI agreed to a government request to defer its building plans, even though a winner of the competition had by then been selected (see previous page). In the changed circumstances of the foundation of the Irish State and a reappraisal of the accommodation needs of the University, the plans for a new building were abandoned. The houses, which had been purchased by the University, were handed over to the State and the potential demolitions were avoided. In 1927, the Merrion Square premises were purchased by the National University of Ireland and accordingly 49 Merrion Square became the permanent address of the University. NUI has been fortunate to have been housed since 1912 in such handsome Georgian buildings and in such a convenient central location. Situated on the east side of the square, no. 49 was built by George Kent some time between the 1790s and 1814. The house was leased in 1818 by Sir Robert Way Harty who was later elected Lord Mayor of Dublin. He is generally credited with having commissioned the mural paintings which are such an important feature of the house. Noting the ‘elegant scheme of mural paintings in the two first-floor rooms c. 1820’, Christine Casey in her authoritative study The Buildings of Ireland Dublin (2005) comments that ‘these are the most ambitious C19 painted interiors in Dublin.’ The murals completely cover the walls of the two rooms from the dado upwards, the mural or murals on each wall being set in illusionistic wooden frames. A study of the paintings undertaken by Marguerite O’Farrell in 1976 shows that the sources and inspirations for the Italianate landscape scenes with classical and mythological references were works by a number of artists including Claude Lorrain and Rubens. |

|

|

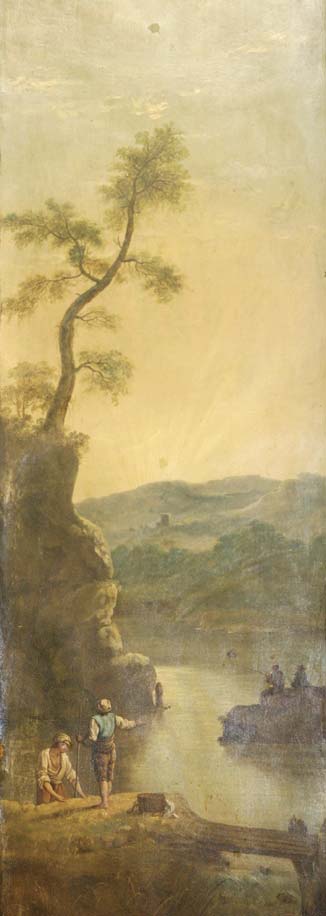

Noting that the paintings were rediscovered in 1946, she identifies seven sources for the murals in the front room, as follows: on the north wall (Plate 1, page 2), a scene in a panoramic Arcadian setting with dancers and musicians is based on the painting ‘Il Molino’ by Claude Lorrain (1600-1682), now in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome; on the south wall (Plate 2, front cover), the mural again features musicians in a landscape and is based on the painting ‘Pastoral Landscape’ also by Claude; the charming mural in one of the fireplace recesses showing a woman holding child under a tree (Plate 3, page 4) is based on the work of Salvatore Rosa (1615-1673)’; of two murals on the east wall, one of cattle at water

|

|

|

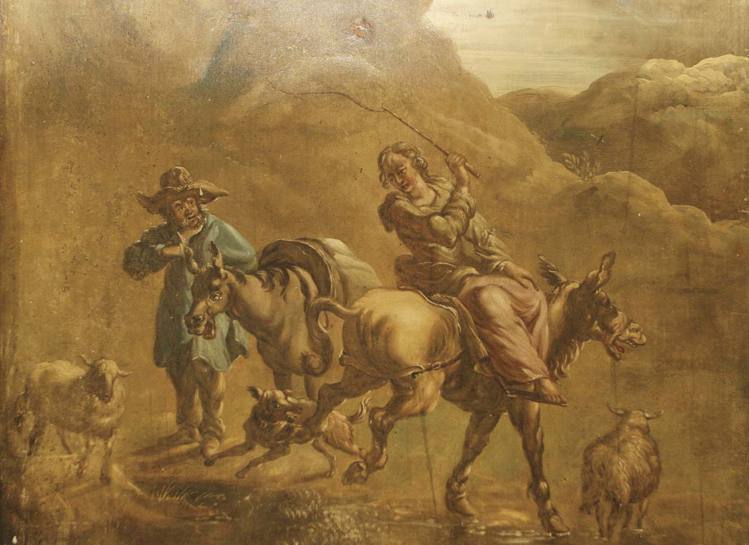

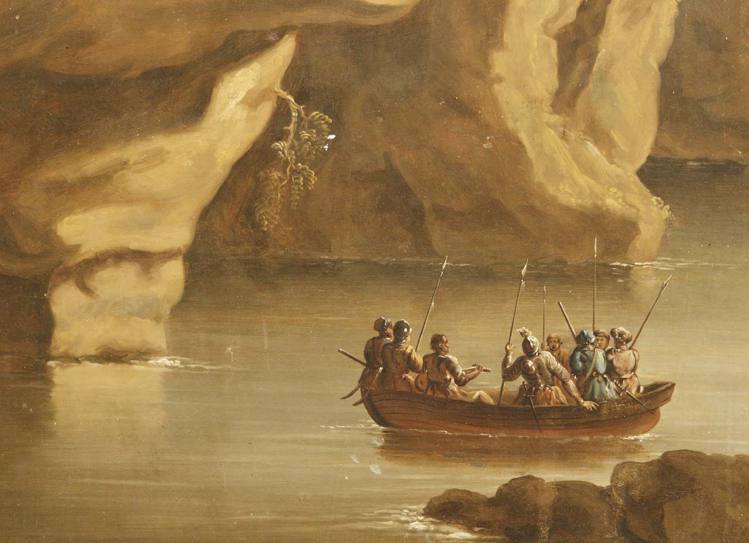

(Plate 4, page 5) is influenced by an engraving of ‘The Watering Place’ by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), now in the National Gallery, London while the other showing a group of soldiers in armour beside a lake (Plate 5, page 6) is from a painting by Jacques Courtois in the series ‘I Banditti’. The two murals on the west wall are in a genre style, one (Plate 6, page 6) from an engraving by Pierre Charles Canot of the painting ‘Le Soleil Levant’ c.1759 by Jean Baptiste Pillement (1728-1808) and the second mural (Plate 7, page 7) is based on the work of Nicholaes Berchem (1620-1683), engravings of whose work were widely circulated in the eighteenth century. O’Farrell also identifies the sources of most of the eight murals in the back room. Again she associates – though not definitively - with Nicholaes Berchem the large mural that fills the north wall (Plate 8, page 8), showing an Italian town with castellated buildings in a leafy setting by a river with fishing boats. The Italian landscape mural above the mantelpiece on the south wall (Plate 9, page 9) is, according to O’Farrell, ‘taken from the painting Castel Gandolfo by Gian Francesco Grimaldi (1606-1680).’ In the recess beside the fireplace facing the door is a landscape with figures based on the style of Jan de Wynants (1625-1684) (Plate 10, page 11). O’Farrell notes that ‘the foreground figures of this mural seem to be painted by a completely different hand to the rest of the cycle.’ In the other recess, the painting (Plate 11, page 12) is based on ‘The Father of Psyche sacrificing at the Temple of Apollo’ by Claude. O’Farrell conjectures, based on some modifications of the original and stylistic similarities which the mural shares with a version of the work by the English engraver Richard Earlom (1743-1822), that the muralist worked from this version. |

The mural on the right of the east wall window (Plate 12, page 13) shows a landscape with figures, one on horseback and according to O’Farrell is similar in style to the work ‘I Banditti’ by Jacques Courtois in the same position in the front room as described above. The painting to the left of the window features classical figures in a hillside landscape. The surface shows the effects of water damage suffered in the early 1990s but was successfully conserved in 2001. O’Farrell notes that two murals on the west wall on either side of the folding doors (Plates Nos. 13 and 14, pages 15 and 16) ‘appear to be in the style of Jacques Courtois and to have Ovidian themes.’ In scale and quality the cycle of mural paintings in 49 Merrion Square is unique in Dublin and is significant in terms of the Georgian heritage of interior decoration. Since they now form part of working offices, these paintings are largely hidden treasures. However, as far as is practicable, NUI is committed to granting access to these delightful works: visits are regularly arranged for art historians and other scholars and access for the general public is provided on particular occasions such as Heritage Week. |

1 NUI Senate minutes 27 July 1909, Vol. I, p.17 NUI Archives 2 Ibid. 28 February 1911, Vol. I, p.201 3 Ibid. 12 May 1911, Vol. I, p. 248 4 Ibid. 26 March 1914, Vol. III, p. 324 5 Ibid. 26 March 1926, Vol. X, p. 29 6 Ibid. 4 November 1927, Vol. XI, p. 29 7 Casey Christine (2005) The Buildings of Ireland Dublin New Haven and London: Yale University Press p. 587. 8 O’Farrell, M. (1976) ‘A Cycle of Late Georgian Mural Paintings in the Senate of the National University of Ireland’ MA thesis UCD. The conclusions of Ms. O’Farrell’s study are contained in a booklet Murals in the Senate Room of the National University of Ireland available from NUI. This essay first appeared in The National University of Ireland 1908-2008 Centenary Essays published in 2008 by UCD Press. |

For further information contact: National University of Ireland 49 Merrion Square Dublin 2 t: +353 1 439 2424 f: +353 1 439 2466 e: registrar@nui.ie Ollscoil na hÉireann 49 Cearnóg Mhuirfean Baile Átha Cliath 2 t: +353 1 439 2424 f: +353 1 439 2466 r: registrar@nui.ie |