30.06.2022

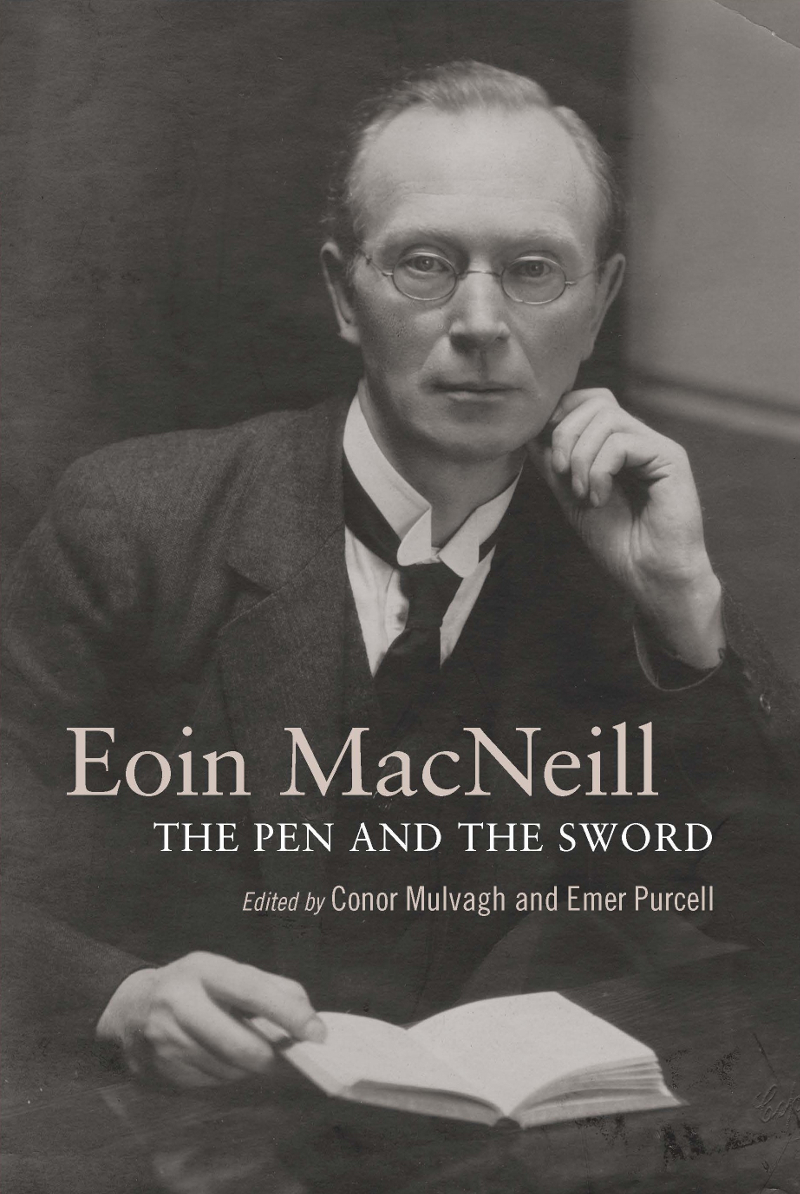

Eoin MacNeill: the pen and the sword launch

Edited by Conor Mulvagh and Emer Purcell

NUI Centenary Publication

21 June 2022

The launch of Eoin MacNeill: the pen and the sword (published by Cork University Press) took place at the National University of Ireland, 49 Merrion Square Dublin, on Tuesday 21 June 2022.

The Registrar, Dr Patrick O’Leary, welcomed all those present to the National University of Ireland and remarked how lovely it was to have people once again in NUI. He then introduced the Chancellor, Dr Maurice Manning, who officially launched the book.

The Chancellor began his address by noting that the National University of Ireland has always been proud of, and has greatly valued, its relationship with Eoin MacNeill. He was a strong supporter of the idea of a national university long before it became a reality in 1908, was a member of the first university Senate and remained an active member and supporter for many years thereafter. He was foundation Professor of Early (including Medieval) Irish History in the university and was elected to the first Dáil from the NUI constituency in 1918.

He sincerely thanked the editors of The Pen and the Sword, Dr Conor Mulvagh, School of History, UCD, and Dr Emer Purcell, NUI. He complimented the publishers Cork University Press for their usual high production standards and thanked Mike Collins and Maria O’Donovan and all the CUP team. He noted that this book is an extraordinary bringing together of eighteen contributors, but also a bringing together of multiple generations of Irish scholars from well-established historians such as Michael Laffan, Dáibhí Ó Cróinín and Diarmaid Ferriter to a new generation including Ruairí Cullen, Brian Hughes, Shane Nagle, and Niamh Wycherley.

What this book shows is the quality and quantity and range of academics engaged in research and scholarship at the highest international level. And in areas where in the past Irish scholars such as MacNeill played pioneering roles, valued by their international peers, and reflecting well on Irish universities when little else did. In this respect all our universities need to examine their consciences. He quoted the editors.

‘Over a century on from McNeill’s appointment as Professor in UCD it is interesting to

survey the institutional standing of Early Irish History across NUI Colleges and note there are

currently NO occupied Chairs of Early Irish and or Medieval history. Extend that search to non-NUI

colleges across the island of Ireland there is one occupied chair-Trinity’s ‘Lecky Chair’.

Introduction, p. 8

MacNeill was a public intellectual long before that phrase came into vogue, and he probably would not have approved of it. He was prepared not just to contribute but to lead on the great public issues of the day: education and the university question; nationality and identity; language; and self-government. Such was his standing, and the genuine respect there was for him, that he was the only politician who could possibly have persuaded a beleaguered and cash-starved administration – and against the entrenched advice of its civil servants – to establish the Irish Manuscripts Commission. It was an unparalleled deed of foresight which did so much to ameliorate the consequences of the destruction of the Public Record Office at the Four Courts.

Emer Purcell began by noting that Eoin MacNeil is much championed as the founding father of the discipline of early medieval Irish history. She acknowledged that while it was difficult to summarise his abilities as an historian, she pointed towards three factors: (1) his ability to read the primary source material, in Latin, Old, Middle and Modern Irish. [And indeed, MacNeill made an immense contribution to the Irish language movement as is discussed in the Language and Culture section of the book]. (2) he had a remarkable ability to interrogate and corelate a wide range of source materials: law tracts, genealogies, annals, poetry, placenames, sagas. And thirdly, as many have commented previously, he had an instinct and/or flair for history.

She noted that not all MacNeill scholarship had stood the test of time. However, if you want to seriously study early medieval Irish history today, you still must start with his work; his essays and lectures which later evolved as edited collections Phases of Irish History and Celtic Ireland. And, in particular, his article on early Irish population groups, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy in 1912, which is still the starting block to understanding kingdoms and dynasties in early medieval Ireland.

She thanked fellow editor, Conor Mulvagh, and the contributors. Noting that it was the scholarship of the contributors that led Seán Ó Coileáin to remark that The Pen and the Sword ‘goes far beyond “a decade of centenary” type of production and ranks as a worthy successor to Scholar Revolutionary’.

Duirt Conor, buíochas a ghabhail le gach duine a thanaig anseo anocht ar an lá is foide sa bhlian agus buiochas a ghabhail don Ollscoill na hÉireann as dídean a thabhairt dúinn anocht agus go formhór as an cabhair agus cúnamh a thug siad don tionscadal seo ó thús go críoch.

Conor expressed his thanks to the Chancellor, Dr Maurice Manning, the former Registrar, Dr Attracta Halpin and the current Registrar, for their encouragement to get this project off the ground and to see it through. He thanked the contributors for the scholarship they brought to bear on the chapters contained in the volume and for their resilience in bringing the volume to fruition through that challenges that the pandemic created. He thanked Kevin Murray, Elva Johnston, Liam Mac Mathúna and Dáibhí O Cróinín for their expert advice and sage counsel at various stages along the way.

He paid a special thanks to the archivists and librarians who both preserved and facilitated our access – both the editors and the authors – to the manuscripts and other sources which all the authors have used so effectively to explore new areas in the life and times of Eoin MacNeill. In some instances, this research was carried out in the early months of the pandemic and these archivists and librarians went above and beyond in facilitating access to sources when we needed them most. The list of these repositories, stretching across Ireland, Britain, and the United States speaks to the reach of MacNeill. Finally, he paid special thanks to UCD Archives who hold the MacNeill and Tierney family papers. In particular, he thanked Dr Kate Manning and her team for their work in facilitating access to the papers and with UCD Digital Library the Tierney-MacNeill photographs which form the bedrock of the plates sections of this volume and are so beautifully realised by the team at Cork University Press.

He noted that personally, he found MacNeill both elusive and sprawling as a subject of study. At various points in the research and editing, he was reminded of Lloyd George’s observation about de Valera that he was like trying to pick up mercury with a fork. At times, MacNeill felt like this too.

Mulvagh observed how there was a generational element to MacNeill’s significance among his younger colleagues during the processes of revolution and state formation. And that looking at the sections of the book on MacNeill’s political life and legacy, something that struck him both in writing for the volume and editing it was that there is a generational aspect to MacNeill’s significance in the Irish independence movement. He observed that on occasion, MacNeill was to the moderate wing of the Volunteers and later Sinn Féin what Tom Clarke had been to the more advanced radicals in the IRB camp: a father figure and elder of sorts.

He concluded, as outlined in this volume, MacNeill was both pessimistic about the prospects of success at the Irish Boundary Commission and yet willing to act as representative to spare a younger cabinet colleague – most likely Patrick McGilligan – the political fallout from association with that enterprise. He remarked that he was not sure he fully bought MacNeill’s protestations about being a reluctant politician. He was certainly not a political operator in the mould of the Irish parliamentary party’s MPs, and he chaffed against them when forced into their company in the early years of the Irish Volunteers. However, he was as much a politician as any of the volunteers turned deputies following the 1918 general election.

The book launch was followed by a reception

Conor Mulvagh & Emer Purcell (eds), Eoin MacNeill: the pen and the sword (Cork University Press, 2022)

Eoin MacNeill (1867-1945) was a founding figure in the Gaelic League, the Irish Volunteers, and the government of Ireland. As Professor of Early (including Mediaeval) History at University College Dublin was also one of the foremost Irish historians of his generation. As a professor, a politician, and the leader of a paramilitary organisation, MacNeill fused scholarship and activism into a complex life that both followed and led the course of Irish independence from gestation to maturation.

This collection confronts the complexities and apparent contradictions of MacNeill’s life, work, and ideas. It explores the ways in which MacNeill’s activities and interests overlapped, his contribution to the Irish language and to Irish history, his evolving political outlook, and the contribution he made to the shaping of modern Ireland.

Copies of the book are available to purchase from all good bookshops and directly from Cork University Press

Tweet

« Previous